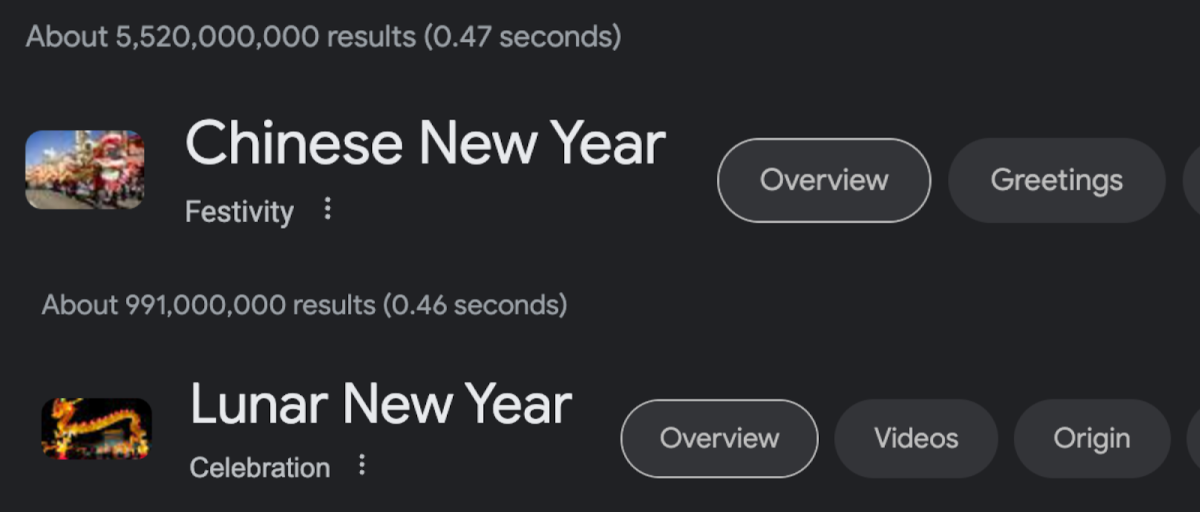

Lunar New Year is an important celebration for many Asian communities. It’s known for vibrant colors, rich traditions and captivating festivities, however, long-standing debates have surrounded the term “Chinese New Year” for years. The question is: should “Chinese New Year” should be considered a synonym for “Lunar New Year,” or is the term “Chinese New Year” offensive to Asians who are non-Chinese?

Firstly, what exactly is Lunar New Year? It is a festival celebrated to welcome the arrival of spring and mark the beginning of a new year on the lunisolar calendar, which is based on the moon cycle and the weather solstice. According to the Lam Museum of Anthropology, the Lunar New Year has its roots in the Shang Dynasty (1600-1046 B.C.), where people held sacrificial ceremonies to honor their gods and ancestors. Later, this practice became an annual custom during the Zhou Dynasty (1046-256 B.C.) when the term “Nien” or “Year” was introduced. Lunar New Year is the most important holiday in China, South Korea, Vietnam and other countries with a significant overseas Chinese population. Although the holiday’s official dates vary by year, it is typically celebrated as a time to reunite with immediate and extended family.

Is the term “Chinese New Year” valid if the Ancient Chinese created the lunisolar calendar? Using a culture-specific term for a festival celebrated by various cultures is naturally problematic. Lunar New Year isn’t only observed in China; it’s celebrated across several countries and other territories in Asia, including South Korea and Singapore. For instance, in Vietnam, the new year is called Tết, which is short for Tết Nguyên Đán meaning “Festival of the First Morning of the First Day.” In Tibet, Losar is the name given to this important occasion, while in Korea, it’s celebrated as Seollal (설날) from Eumnyeok Seollal, “Lunar New Year.” Interestingly, the “Chinese New Year” controversy only exists in the English-speaking world, where the festival was first observed by Westerners in China. Chinese people referred to this Festival as Chūn Jié (春节), where “Chun” stands for Spring and “Jie” stands for Festival. The term “Chinese New Year” only became a “thing” when the Spring Festival was introduced and popularized by the largest segment of the Asian-American population in the U.S – the Chinese community.

In principle, the festivals of Chun Jie, Tết and Seollal all resemble one another in some way. Especially when these three festivals are celebrated in cultures that have traditions of exchanging red envelopes, gathering with family, enjoying large meals and observing superstitions. Despite the similarities, differences also exist in these Asian cultures – while the Spring Festival lasts up to 15 days in China, Vietnam’s Tết goes for up to a week and Seollal for Koreans only runs for three days. Another difference is their traditional food; for instance, noodles are a must-have dish in Chinese cuisine, where the length of the noodles symbolizes a wish for longevity. On the contrary, bánh chưng (chung cake) – a cake made of sticky rice, meat, and mung beans wrapped in dong leaves is a signature dish of the Vietnamese New Year tradition. This cake is a perfect example of Vietnam’s agricultural heritage, expressing respect and gratitude towards ancestors and the source of life. On Seollal, Koreans eat a special soup known as Tteokguk or Rice Cake Soup. This soup is eaten to wish for good luck, prosperity and wealth in the upcoming year where the shape of the rice cakes used in the soup resembles that of old-style Korean coins, symbolizing the hope for riches and prosperity in the new year. Despite common traditions, these three examples demonstrate the different ways in which the Lunar New Year is celebrated across Asia; however, the problem arises when all three are thrown under the blanket called “Chinese New Year.” The term, in its purest form, implies that this holiday is exclusive to China and the Chinese people.

So, is the term “Chinese New Year” still valid to use? Again, the answer is both yes and no! Technically, there is nothing wrong with calling it “Chinese New Year”; the only problem is how the Western world portrays this celebration and uses this term as a synonym for Lunar New Year. By casually calling this particular occasion “Chinese New Year,” we had labeled a celebration associated with many other East and Southeast Asian cultures into just one specific ethnic group. There is no problem if you say “Happy Chinese New Year” to your Chinese friends, but it will be a major problem if you apply this term to other Vietnamese, Korean or Mongolian friends who are also celebrating this festival in their traditions. It’s disheartening to see our significant cultural event being labeled solely based on European-centric naming conventions; this feeling is like being called “Chinese” based on my Asian features. At the end of the day, Chun Jie is still Chun Jie, Tết is still Tết and Seollal is still Seollal; having a branch from a common culture is great and worth inheriting regardless of the current political or ideological situation. What Lunar New Year means is more important than what it sounds like.